Being made by place

On belonging, longing, interbeing, more-than-human friendships, and a love letter to the mountain

I breathe with the mountains.

I breathe with the trees.

I give and receive.

I become you, and you become me-

this is our interbeing.

Dear beloved Enchantable readers,

Last week I returned1 to another home, Colorado Springs, where we lived before moving to Costa Rica - our home for four years, where Daphne lived from ages 0 to 4, the place she thinks of as home. So many baby Daphne memories were made here.

As I return, I am thinking about the places that make us, how we are made by place, and how we make a place by being in it. Sometimes maybe we can only get this perspective, by how much a place is a part of us, from the gift of leaving and returning.

I am thinking about home, and what it means to belong.

As soon as we stepped off the plane, you could feel the power of the mountains, their magnificence, majesty, beauty, force. Colorado Springs is where the Great Plains meet the Rocky Mountains. A stunning geography: the east, flat for days; to the west, the 14,115 peak of Tava, Sun Mountain, as named by the native Ute (also known as Pike’s Peak, for a guy who never climbed the peak), looming large over the whole region. The view from the top inspired professor and poet Katharine Lee Bates to pen the words in 1893 that became the anthem American the Beautiful. The airport is in the plains east of the city, and when you land, you have a very dramatic view of the mountains to the west. As you move about the city and surrounding parks, everywhere you look you can see Sun Mountain, and everywhere you see it, you get a slightly different view, getting to know the mountain from different angles and perspectives.

We have arrived, we are home.

I begin to notice how my body feels like it moves through space differently here, like it can move through the air with more ease than in the tropics, where it is weighed down by the dense humidity. There is a lightness in cutting through the dry, thin mountain air. I feel like I’m gliding. Meanwhile, in this air, my skin immediately dries up, cracking and rashing, begging for moisture, whereas in Costa Rica I barely use lotion.

I notice my relationship to the sun: how in Costa Rica, I am usually hiding from it, actively avoiding it, seeking shade; how here, in Colorado, I am basking in it when it comes out, thawing out, trying to warm up under its rays, which in early spring still feel so far, barely warm.

I notice how my hair does something completely different here. It loses all of its curl. I had forgotten I had wavy hair after living in Colorado Springs for four years. Upon arriving to Costa Rica, I was reminded. My hair immediately sprung up, took on waves in the humidity.

All of this has me thinking about how the things we think might be “essentially us” - our dry skin, our curly or straight hair, the way we move - actually might have a lot less to do with us than we think, and more about where we are. How they actually have so much to do with the conditions we are living in, the environment we live in, the land and air. It’s us in the world. It is the world shaping us.

What other things might we think are essentially us but are actually because of the interaction between us and our environments, the land, the climate, our consumption patterns, our habits?

What does this mean for those of us who live in places different from our ancestors? What does it mean for us, living on a warming planet with a changing climate?

How would our relationship to the earth change if we understood at a deep level that we are made by it and making it at the same time?

“There is a lot of you in these mountains,” my friend said to me.

I hadn’t thought about it that way, specifically. I had been thinking about how there is so much of these mountains in me, and how I take them wherever I go. But I hadn’t thought about how much of me was in these mountains. Of course, from the point of view of the insight of interbeing, this makes perfect sense. “Because I am in you, and you are in me,” say the lyrics of a Plum Village song.

The time I lived in Colorado Springs was beautiful, and also the most challenging years of my life so far, largely marked by pandemic solo parenting while grieving, as I have written about before. This is where I was when the pandemic started, and we had moved here only a few months before. I was living here when my mom died, and so many of these trails hold the grief I was carrying and processing during those years as I walked the land with my heavy heart. Meanwhile, I was writing a dissertation, writing it with the mountains and the trees and the coal power plant at the edge of my neighborhood, with the coffee shops that held much of the writing.

The power plant stopped running at the end of our time living here and started the decommissioning process. Our neighborhood began organizing to try to ensure that the community’s voice is heard in the plans for what is done with the land once the power plant is decommissioned, a lengthy process. I had a joyful lunch with the neighborhood organizing committee to catch up with each other. It tells you everything you need to know about the neighborhood to know that they organized a lunch for me upon our return. Once a Mill Street neighbor, always a neighbor, it feels like.

It was striking to see the start of the demolition of the old power plant. Looming over the city too, a massive toxic landmark, beginning to crumble, symbolic of old ways dying, but whether their death will make way for something more liberatory remains to be seen.

The plant, for me, was always a reminder of the interbeing we don’t necessarily want to see or acknowledge. I am writing and breathing and being with the mountains - yes, that is easy and inspiring and beautiful. But I am also writing and breathing and being with the coal-fired power plant, with all of its toxic pollution. It powered the heat in our homes amidst the frigid winter. It powered the energy for the laptop I wrote on.

Giving power no more, it is being torn down, undoubtedly releasing toxins in the process. What it will become remains a mystery, as the neighborhood tries to fight for a community benefit agreement to ensure that it doesn’t just become another luxury high-end apartment building like seemingly every other lot in the city. Upon returning, I was shocked by the number of apartment buildings that have sprung up in this year and a half since we left, which seems to have done nothing for the houseless population still living in tents, freezing down by the creek.

The power plant, in its state of demolition-in-progress, is a visual and visceral reminder that old stories are crumbling. There are other ways of being and living, ways in which everyone has their needs met, shelter and food and warmth. Other ways to generate the electricity we need that don’t pollute the air we breathe. As these old stories crumble and are demolished, may the stories of the mountains guide us towards more life-affirming ways of living.

We inter-are with the mountains, the trees, the crisp air, both fresh and polluted at the same time. We inter-are with the looming majestic peak and the looming demolishing power plant.

I was about to head out the door when a friend texted. “I can meet now,” she said.

But I couldn’t. I already had other plans with other friends - with my friends the mountain, rocks, and trees.

It occurred to me to cancel. I was just planning on visiting Garden of the Gods and a tree on the Greenway bike trail, places that were special to me during my time living here.

But I already had plans with friends. They were just more-than-human friends. I couldn’t cancel on these friends any more than I would cancel on a human friend. I’d like to think they were expecting me.

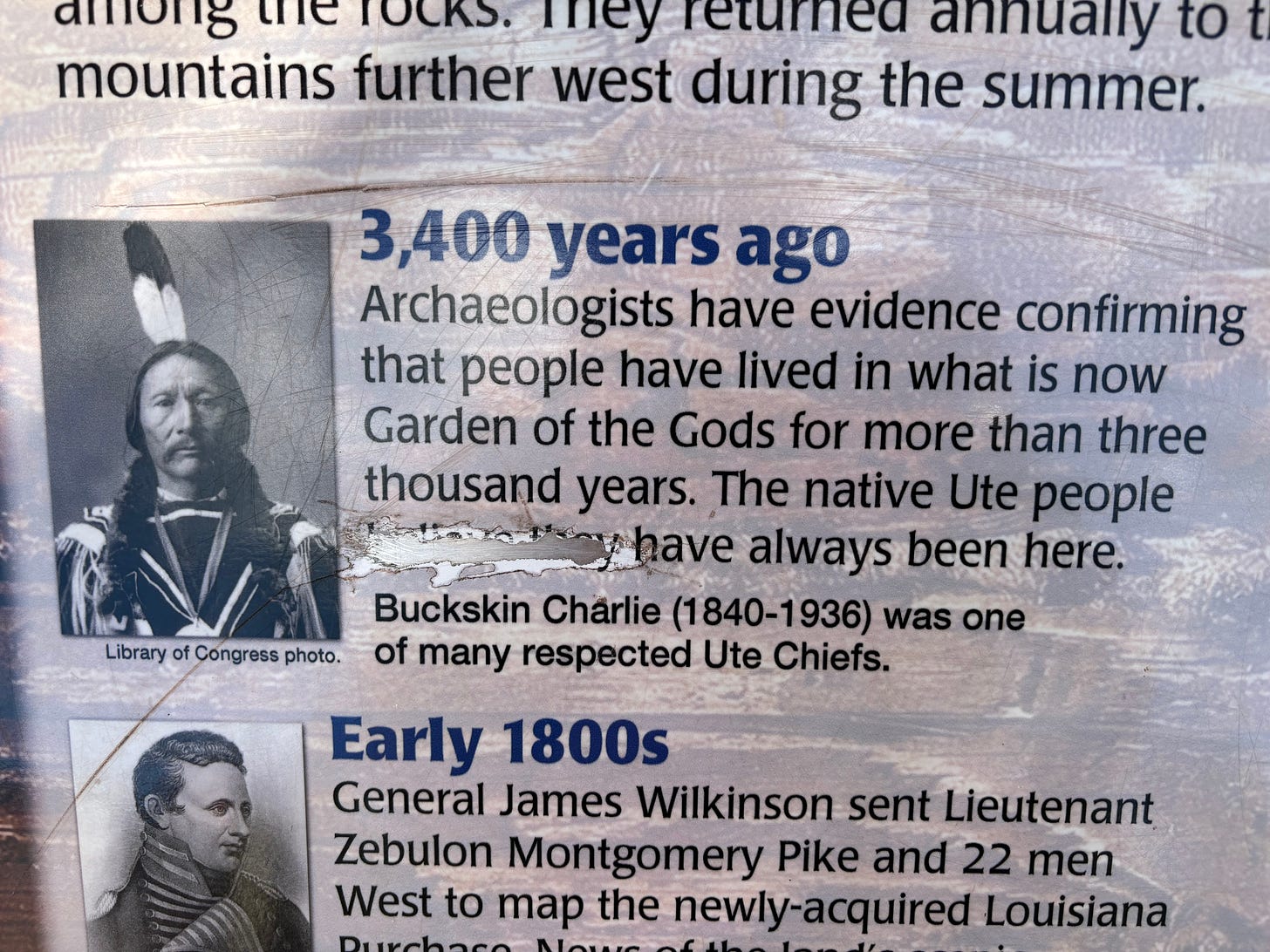

I headed to the Garden of the Gods Park, a public park and sacred site for the Ute nation. The rock formations are more than 300 million years old, a time frame nearly impossible to wrap a human mind around. The Ute have always lived there, and this is the site of their creation story. This “graffiti” on one of the park signs corrects the history: The native Ute people have always been here.

I went to the central garden, the most touristy area of the park, for good reason. To walk among the ancient towering rock beings is magical.

How would our relationship to the earth change if we could remember that they are beings, and not dead, intert matter? They are not “it,” they are wise elders?

How would our relationship with the earth change if we could think, dream, and live on a scale that understands hundreds of millions of years, deep time?

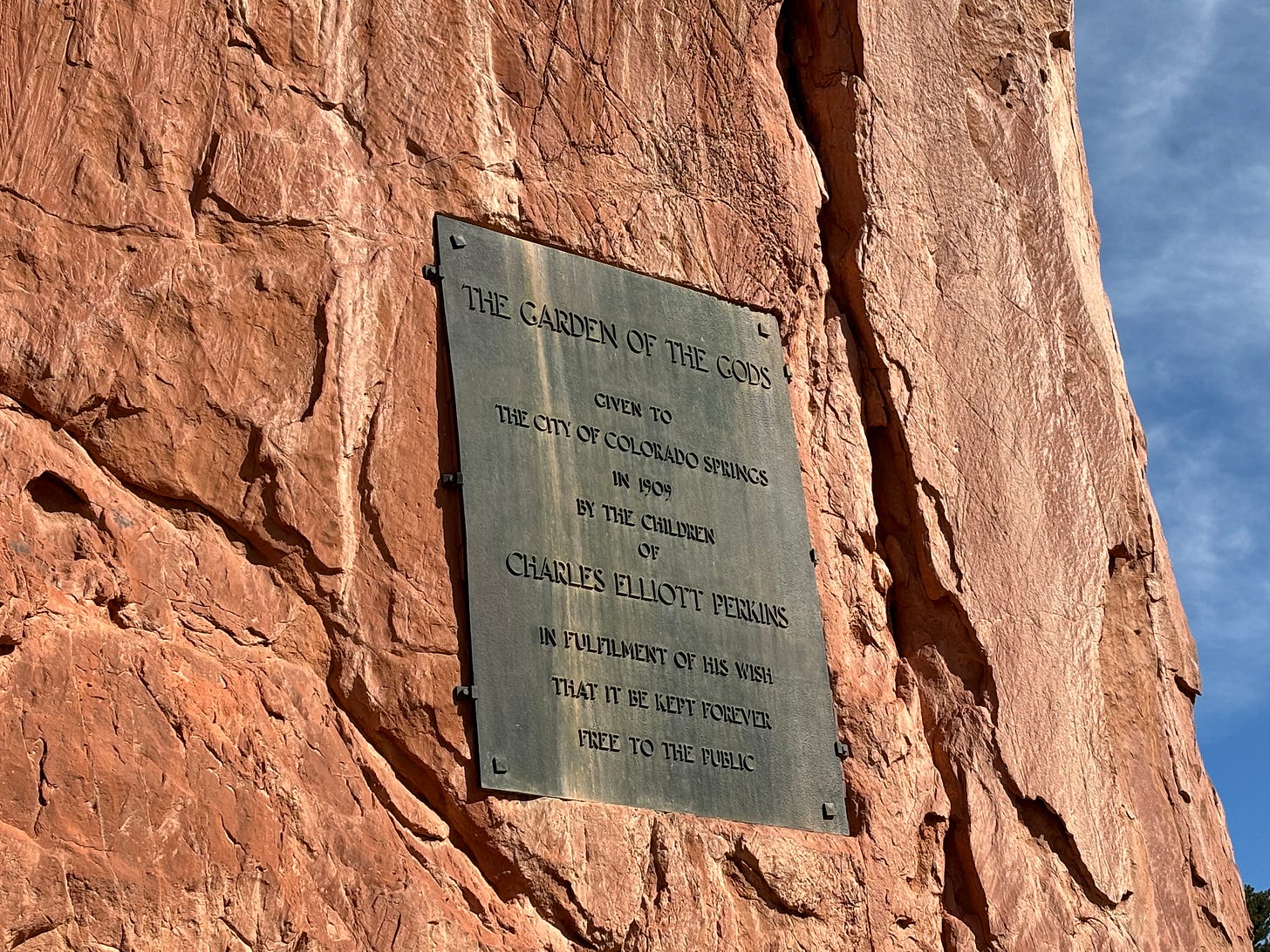

I walk by the stone in the central garden with a plaque that reads: The Garden of the Gods, given to the City of Colorado Springs in 1909 by the children of Charles Elliott Perkins in fulfilment of his wish that it be kept forever free to the public.

This stone always bothered me. But it wasn’t yours to give. In the meantime, the Ute were forcibly removed from this land, which is still their land, and relocated to reservations in southern Colorado and Utah.

It reminds me of the campus where I teach, the land for which was “given” to the United Nations by the government of Costa Rica for the establishment of a University for Peace. But it is Huetar territory, and it was not the government’s to give.

What do we do with these places, that were given but they weren’t ours to give?

How can we begin to make peace on unceded occupied territory, as uninvited guests?

I stopped to visit my favorite tree, an American elm located near Colorado College along Fountain Creek on the Greenway bike path. On many pandemic days when I had childcare, I would leave Daphne at home with her babysitter and bike to a coffee shop and sit outside, trying to keep a safe distance while writing my dissertation. On my way home, I would stop by this tree and sit under its giant boughs. We spent a lot of time together, me and this tree. It held me through a lot.

It wasn’t like visiting an old friend - it was visiting an old friend. This tree and I shared so much. We saw each other through many seasons. It helped me find roots, stability, groundedness in a very turbulent time of my life. I left a stone from Costa Rica in its trunk, a small offering.

I continued along my visit, returning to the neighborhood coffee shop where I wrote much of my dissertation. I was so warmly welcomed and the staff who I knew from before were genuinely happy to see me, and I them. I left them a Costa Rica rock with a sloth on it, another offering, another beautiful trace left along the journey. I met a friend for coffee and lunch, like old times, like I had never left.

I belong here, a deep feeling of belonging, the place and the friends, both human and more-than-human, the neighbors, and people happy to see me upon my return. But I also belong where I live now.

Be-long. I can’t help but notice the longing in the word, and how once we belong somewhere, we will long for it when we are gone, when we are away from it. I can love where I am now and long for these mountains. Daphne does. She longs for Colorado when we are in Costa Rica, and longs for Costa Rica when we are in Colorado. We belong in both places, but we can only be in one place.

Yet we carry both places with us (and so many more).

We are made and make both places.

Both places have made us, and we make both places, even when we are gone.

Parts of us remain in the mountains as we carry the mountains in our hearts.

In ten days or so, we will return, having been made by these places over again, carrying them within us, continuing this cycle of being made and making and unmade, together.

On the cusp between winter and spring, the first blossoms appear on the trees.

I write a love letter to the mountain.

Dear mountain, Sun Mountain,

Thank you for always being a home to me. Thank you for receiving me upon my return. I am in awe of your beauty and magnificence, and the power with which you hold this place and all around you.

I am in awe of how you stand, so grounded. I remember during the early pandemic when things went into lockdown, wondering what you thought about us, knowing you had seen it all, hundreds of millions of years of history, and us humans and our cars and rushing was just one tiny blip, perhaps an anomaly.

You have held me in my joy and grief. So much grief I left with you in the mountains, as I hiked and sought solace in your sturdiness and stability. You have given me so much. I take refuge in your beauty.

I have felt so much joy in my steps walking around your foothills, in the forests and among the trees that drape you in beauty. I am delighted every time I see you, like a crush or someone you are in love with. Because I am in love with you, dear mountain.

You are also a teacher and a friend. You teach so much about grace, beauty, power, groundedness, stability. You are there for us, and all we have to do is be attuned to your qualities, your magnificence. All we need to do is pay attention, and you are there to receive us.

Like a good friend, you have held my stories. Have I done enough for you, dear mountain? I have received so much…have I given you everything I could?

You also continue to hold my many beloveds here, our friends-like-family who still live here. Please watch over them and nourish them, protect them, and remind them they are loved while we are gone.

I am grateful, so grateful, for your existence and for our relationship. I carry you with me as I go, in my blood and bones and skin and heart. I know I just have to remember you to receive your power and stability. Thank you for being a part of me. I leave some of myself here with you, to be a part of your ongoing story, which is my story, too.

With love,

Stephanie

This post is an extension of my January essay, many returns, which you can find here: